Inscryption

The Review

Play Inscryption.

The In-Depth Review

Inscryption is a weird-horror-themed deck-building roguelike from Daniel Mullins, the creator of the weird-horror-themed Pony Island and The Hex, which I haven’t played but I’m guessing is weird-horror-themed. Ostensibly a simplistic card game with a swampcore theme, it quickly unfolds into something more complex as you master the ruleset.

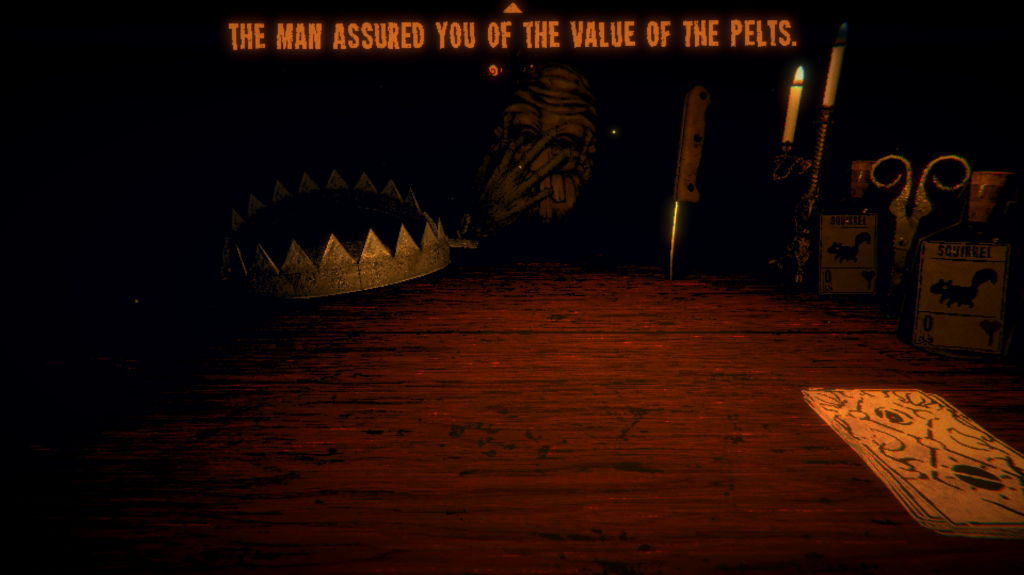

When it begins, you’re greeted by Leshy, who serves as your game master — he deals cards, explains rules and puts on creepy masks to play the role of other characters in the game — the bosses like the Prospector or Angler, and Traders like the Trapper or Trader.

But deep down you know something is off here. There’s something very sinister about how Inscryption plays. The scoring system, where you need to do +5 points of damage — that is five more points of damage than your opponent — uses gold teeth as its scoring marker. And you can lean on the scales with a pair of pliers and some impromptu amateur dentistry. And that’s all in keeping with the theme of the game — but things get weirder yet.

Some of your cards, for example, talk to you. Not a lot. One of them only pipes up to tell you you’ve misplayed. And you can get up from the table, which is far outside the norm. There are other puzzles for you to complete while you wander around the small cabin you’re trapped in, and Leshy stares at you eerily while you pixel hunt your way through the small room.

You find new cards, and you unravel the secrets of your location, but at its core Inscryption is still a card game — and so you return to the table to play more cards.

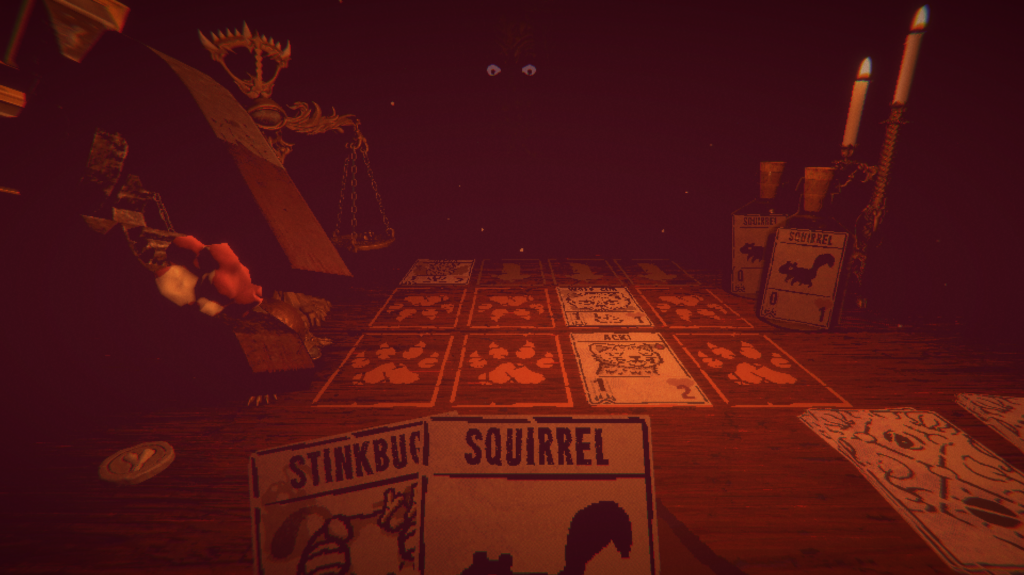

I wouldn’t say it’s a great card game. It cheats, for example. That is to say, if you win when you aren’t meant to, it will simply tell you that you have lost, declaring “Too Fast, Too Soon” and resetting your run. And when it’s not actively cheating, it’s just feeling unfair by throwing mechanics at you that you can’t do anything about if you haven’t seen them before. Board clears that leave you defenseless require prior knowledge to accommodate for, but they happen out of nowhere — and when they occur at the end of a run, it makes the last 30 minutes feel like a waste of time.

And it cheats in the other direction, too. The Roguelike element of the game involves building up a set of cards that are so hideously overpowered that defeat is nigh impossible without being cheated, which almost makes the cheating okay.

The game thrusts cards at you, but you can’t opt to not take them, which means you learn to build a path through the game that either destroys cards or simply never acquires them in the first place. This creates RNG heavy scenarios where you might not really have the cards needed to forge a path to success, and you’re instead burdened with a glut of garbage that will inevitably lead to failuire. It results in layer upon layer of RNG — which is how deckbuilding roguelikes work — but your mitigation techniques don’t feel as robust as they do in other games of the genre.

It reminds me of Monster Train at launch a little bit. That game had a problem with vulgar displays of power — it was possible to scrape out an unlikely victory, but if you wanted to guarantee the win you’d play Umbra and feed a unit until defeat was a literal impossibility. It removed nuance from the game — although over time Shiny Shoe fixed this issue by slightly nerfing a few Umbra units and then buffing everyone else.

When this happens, you’re able to call your victory from a long way out because your path to victory is very narrow — and that is the case in Inscryption. It results in a bit of a tedious grind as you wipe and restart once you’re certain your win conditions can’t be met — which isn’t really in the spirit of the game (or genre), but is far more efficient than playing out a known loss.

It results in an experience that is far more compelling than Pony Island, but very similar. There’s a ‘wall’ that you need to overcome, much like in an Idle/Incremental Game. In Pony Island this wall was doing the same few puzzles for longer than I felt was reasonable, in Idle Slayer it’s killing 50,000 blue fires to unlock an item, and in Inscryption it’s cycling through 0% win chance runs to find a viable path to victory.

What Inscryption does better than Pony Island, however, is drip-feed the lore and story elements to you while you grind your way through these non-viable runs. There’s loads to discover in Inscryption’s cabin, but clean area design means it’s easy to keep track of what you’ve unlocked so far. Like a single room metroidvania, there’s a spark of excitement when you realise you’ve unlocked something that will finally allow you to interact with some mysterious object in the cabin.

And the truth is, while the Slay the Spire dork in me raged and howled at the nature of the card game, it quickly became obvious that the card game isn’t really what Inscryption is about. The cards are just a mechanism to keep you at the table, but Inscryption is really about the mystery at the heart of the cabin.

Like all really good mysteries though, I basically can’t mention any of it without generally spoiling the shit out of it for you, and so I will not.

Instead I will say I think despite my qualms with the RNG-ness of the card game at its core, Inscryption’s narrative is worth the effort. Play Inscryption.

The In-In-Depth Review

Fair warning, there are spoilers below.

I’m not kidding. Beyond this picture is spoiler territory (although I’ll still try to keep it light).

Like Daniel Mullins other games, Inscryption is more than just the swampcore deck-building roguelike it appears to be from the outset. It remains a deck-builder to the end, but Inscryption uses Full-motion Video to tell a meta-story about a card collecting youtuber who finds a copy of a game buried in some woods. It tells another story about an evil video game that has designs on world domination, though I don’t think it’s an artificial intelligence story.

It changes formats multiple times, and introduces three more wildly different card mechanics — and attempts to blend all of these together as well. But at its core it remains a puzzle game. I think the RNG aspects lessen as you get deeper — maybe a concession to the complexity of the melded card game elements, maybe an admission of fault regarding the success of that melding — which means the card game remains front-and-centre superficially but takes a backseat to the puzzle game.

It gets more successful as it continues, in my opinion, because it’s not bogged down by the imbalance at the core of the card game. You’ll still lose a few battles unnecessarily, but that’s ok — I don’t think anyone expects to win every card battle, I just think I should win the ones where I know I’ve set myself up for success.

That actually brings me to the key element of this Double Deep Dive — P03, the robotic character at the core of the game’s third act, is obsessed with ‘perfect play’, and their dialogue is written like a skewering of the concept. As if an obsession with playing ‘correctly’ is a fault in and of itself.

Or maybe I just feel that way because I self-identify as someone who appreciates or prefers correct play, who self-optimises strategy. Maybe I’m overly defensive about it. That’s certainly possible.

But I feel like there’s a deep irony in the idea that P03 declares that he hates it when narrative gets in the way of perfect play. He is the representation of, I think, a sort of obnoxious min-max style gamer who cares little for story — something I’ve been accused of often. Like I said, I might be overly defensive about this. But Inscryption and Pony Island are both games that I feel suffer at the hands of imperfect systems, and those imperfect systems hold their interesting storytelling back.

And I think that’s something that we don’t account for with games all that often. The idea of certain things being ‘immersion-breaking’ is common but rarely related to systems. Planes teleporting across the screen in Battlefield 2042, the magic back pocket of first person shooter characters who store a rocket launcher… somewhere — these things take players out of the game when noticed, but they’re largely inconsequential.

But systems can break immersion too. Especially if immersion is simply the act of being driven to distraction in playing a game more (and I know it is more, but bear with me), a game ruining that flow with an imperfect system is far more detrimental to a game’s narrative than a player not caring to engage with the narrative in a meaningful way.

With that in mind, I don’t think Inscryption’s systems are as flawed as Pony Island’s. Mullins shows tremendous growth between the two games in my opinion, both in game design and storytelling. The puzzles are far more compelling, the base gameplay more interesting, and the mysterious tale told across the many layers of the game had me obsessed.

And so what if I think the game might be taking pot shots at my playstyle? The real truth is that I know there are mysteries I left uncovered within Inscryption. There were puzzles I didn’t solve before I finished the game, coddled as I am by games that (immersion-breaking as the habit is) tell me outright to make sure I’ve finished any side quests because I am about to pass the point of no return. How, then, could I know if my defensive reaction to P03’s characterisation is accurate? What if I misread it, self-conscious as I am about being obnoxious, and the truth lies in a reading by someone less self-absorbed than me?

There’s only really one way for you to find out the answers to these questions. Play Inscryption.