Neon White

I don’t like “visual novels”.

I have to get this out of the way early, because half of Neon White is a visual novel.

I’ve enjoyed a couple of them. I found “I Love You Colonel Sanders” amusing in its earnestness, although I felt its attempts to lampshade its product placement more akin to Rick from “Rick and Morty” staring directly at the ‘camera’ and asking for a Nintendo 3DS than it was having Britta from Community fuck the human embodiment of Subway.

I still think about Doki Doki Literature Club from time to time, a game which subverted expectations of the visual novel genre to create a psychological thriller where the player is a victim. And yes, I said player — not player character.

But in general the visual novel genre doesn’t work for me. It’s a problem of pacing and interaction. While many games automate the process to some extent, some refuse to — because in some cases tapping a button to progress to the next sentence is the only interaction a player will have with the game.

But I don’t want to read a story by clicking once for every sentence, I don’t feel the visuals enhance the storytelling a meaningful amount, and I find it difficult to connect to the player character when they are presented in this manner.

So, bear this in mind when I tell you that Neon White is very, very good. And bear it in mind further when I say that the visual novel aspect is bad not just because I think visual novels are bad, but because I think the visual novel specifically is a poor storytelling method for a game like Neon White. I recognise that I don’t like visual novels, but even accounting for that — even if I picture myself enjoying them — I think Neon White would be better suited using almost any other storytelling method. (I say almost because ‘unskippable cutscenes’ would be worse, as they are worse in literally every situation ever).

First off though — what is Neon White?

Put simply, imagine The Gauntlet from Titanfall 2 — a fast-paced speedrun challenge level where players must combine expert first person platforming with precision shooting. Now imagine more than 100 different Gauntlets, each one a puzzle for players to solve, where you must shoot all the targets — in this case ‘demons’ — and navigate all the obstacles as fast as you possibly can.

You’ve got two weapons, and (almost) all of them have an ‘alt-fire’ ability that enhances your platforming in some way. The trick, however, is that when you use that alt-fire, you discard the weapon, effectively using up all of its ammo for that one move. The essence of the game boils down to knowing how and when to use your weapons as movement assists, and when to use them as, well, weapons.

With a leaderboard that compares your times to your friends (and the world) and a medal system to give you some idea of how well you’ve done, Neon White creates an addictive and compelling parkour game that will have you retrying levels over and over as you attempt to work out how other people scored the times they did.

And then it wraps it in a visual novel.

What makes Neon White work as a parkour game is how quickly you can try again. I didn’t see the tooltip telling me I could retry a level with the “F” key until I was 3 missions deep, but even when I was hitting escape and clicking “retry” manually, I still found it snappy enough that it didn’t disrupt my flow.

But everything changed with the F button — suddenly any aspect of my run that I didn’t like saw a quick tap of Foxtrot and I’d be starting again. It actually became a little too easy — at one point I caught myself tapping F when I’d actually nailed the jump I had intended on making, but I was so used to missing it that retrying had wormed its way into my flow state.

Only a few games have done that. Super Meat Boy is probably the best example, a game where I would happily abandon my current run if I felt I was even a single pixel off target — and also sometimes when everything was perfect, but I’d fucked up so many times prior that it was a now a force of habit. Skate was another, although with the Hall of Meat fucking up was often my intention.

That’s the good shit to me. That’s what I want from a puzzle platformer. What made Celeste click for me was, in fact, the Skate analog — a good run in these games is like a perfect line, where you work out your path beforehand and then you keep eating shit until you nail it.

Neon White does it too. It’s refreshing, because too many first person shooters punish players for optimising. In games like Doom 2016, what you wound up doing was optimising the fun out of the experience — you knew that grabbing the super shotgun and using it to murder everything while running backwards through a level was less enjoyable than switching weapons constantly while you ripped and tore, but it was so much more efficient that, for a certain type of player, it was the only way to really play.

Doom Eternal obviously fixed that, but in Neon White the concept is baked into the core of the experience. Deaths don’t matter, except for the few seconds it might cost you, so you’re free to experiment with all manner of wild theories. If you could save yourself a few hundredths of a second by flinging yourself off that ledge and into the abyss, only to latch on to a wall with your rocket-launcher-turned-grapple-hook at the last second, wouldn’t you do it? And if you can’t make the jump, maybe you can rocket jump over first.

The level design is top notch, too. Early you’ll find that Neon White wants to show you the correct path, and it does it with very obviously placed enemies that seem to scream “you’re going the right way!” But as you familiarise yourself with the language of NW, you’ll start to instead look for the absence of enemies — because these are the locations you don’t need to visit at all. Why go there if there are no targets to shoot, right?

So often you’ll build a mental picture of the map you’re on, charting out the positions of enemies across it to determine your best possible path, and when you finally decide to give that run a shot you’ll find the level designers anticipated your actions and have either helped or hindered you.

Eventually you learn the language of the level designers, and you ‘think’ in Neon White’s terms. I played a few long sessions of Neon White, and when I was really into it I was acing levels on my very first attempt. I was beating people on my friends list by three-plus seconds without having seen it before.

Don’t get me wrong, I went back and I optimised those levels even further, so that my so-called friends wouldn’t be able to beat me without some god damn effort. But when Neon White is firing on all cylinders, you don’t really need to.

And then the visual novel stuff kicks in.

At the top level, Neon White has an interesting enough story. You’re a bad ass person who was sent to hell, but you were yanked back out at the last second to run some errands for god. If you’re good enough at those errands you’ll earn yourself a spot in heaven — at least for a time.

You’re the titular Neon White, so called because you wear white, or something, I don’t super know. My interest in the story dissipated long before I learned if the game gives details regarding the colouring system.

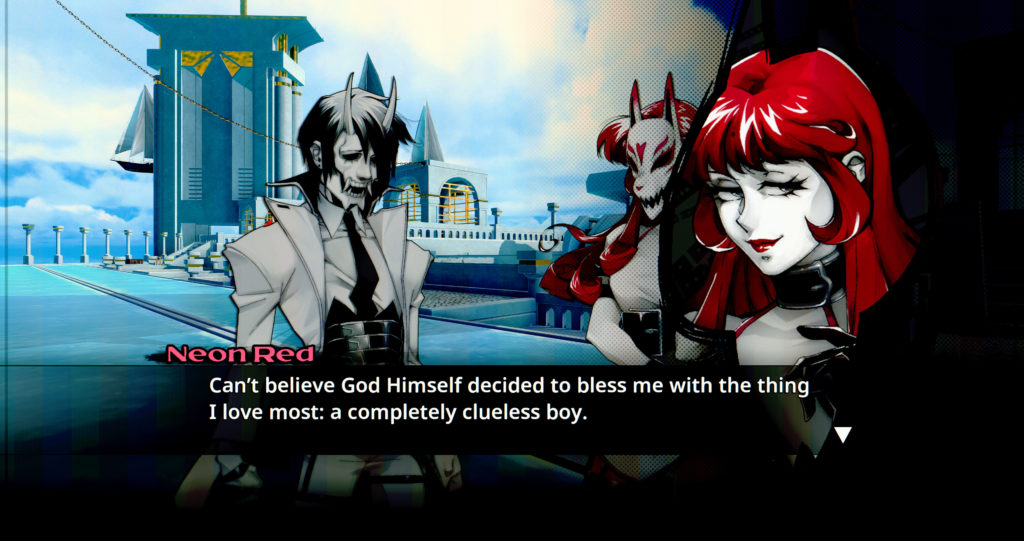

There are other Neons, all of them vying for the same reward you are — a temporary spot in heaven. Some of these Neons you don’t interact with, but some of them are your friends. Unfortunately, you have amnesia, and so you’re forced to work out the details of your relationship with these people based on context clues. Neon Yellow, Violet and Red appear to be quite close to you, but there are others in the mix as well.

The story is told in traditional visual novel fashion, with the player interacting with characters and then clicking through, sentence by sentence, as the often expository dialogue plays out.

I felt the game was punishing my efforts in the puzzle platforming aspect by tying success to more clicking. I hunted down some of the present boxes littered throughout the game — an interesting element where players are challenged to reach areas of the map that are otherwise No Man’s Land — but stopped when I realised I was only earning myself more visual novel clickery.

Still, I feel my bias is showing here — I don’t like the genre, and I am predisposed to be critical of it.

But I do genuinely think, curmudgeonly complaints aside, that the visual novel is an ill-fiting storytelling method for a game like Neon White.

If Neon White is a game about flow, the visual novel clickathon is its mortal enemy. It’s slow, it’s unevenly timed, and it’s not mentally stimulating in the same ways that the core game experience of Neon White is.

Gone is the ability to fail fast. Instead you have two options — you can either click through the dialogue at a pace dictated by the game, or you can press F and blitz through it at lightning speed, like you’re playing Moviedle for a film you’ve never seen, an incomprehensible smattering of half-understood scenes and barely recognised elements.

Choose the latter and good luck working out the story of the game. If you choose the former, flow goes out the window. You can’t even rhythmically click your way through the dialogue, because each sentence takes a different amount of time to play out. Each conversation is of varying length as well. Almost all of us have had to work from home at some point in the last two years — these conversational elements are the video game equivalent of a neighbour deciding to drill just as you finally got into a good headspace to knock out some work. You don’t know when they’ll end, you can’t do much about it, you just have to wait for it to finish so you can get back to your job.

And I think this would be the case even if you deeply enjoyed the story and the way it is told. Because the visual novel style just isn’t engaging the same parts of the brain that the First Person Parkour gameplay is. But I might be wrong. Maybe, for people who enjoy visual novels, those elements present the perfect respite from the heart-thumping pace of Neon White’s missions.

Still, as I blitzed through the game in three sittings I couldn’t help but notice that my leaderboard shrank with each mission. I’d finish Acing a set of levels (and beating everyone on my leaderboard), click through the after-mission dialogue, start the next one and then find one fewer name on the list. They’d often post up a bad time on the first level of a mission and then disappear, seemingly forever.

And hey, we’re all busy. Not everyone can sit around all weekend playing a game they hate half of. But I can’t help but wonder if, perhaps, flow broken, they found themselves struggling to get back to the reflexive state they’d been in previously. And if they bounced off the game as a result.

And if that’s the case, then my theory would be correct. But I might be wrong. There are lots of reasons people stop playing games.

Whatever reason they had, I’d tell them to return to Neon White. To finish the game out. Some of the best levels in it are right at the end, lengthy, minute-long slog fests where failure doesn’t just cost you a couple of seconds any more, and you’ll draw on every single thing you’ve learned in NW to save a run just to learn what is going to fuck you up around the next corner.

You’ll be so balls deep in the flow that you’ll think you’re Jenova Chen, and then you’ll finish the level and earn a silver. And you’ll be happy to have managed that. Then you’ll immediately try that same damn level again and knock two minutes off your previous time and you’ll feel like a god.

And if you don’t finish Neon White, you’ll never learn the truth about Mikey, the only character I cared about in the game. At the end of the day, while I didn’t care for the method of the storytelling or the bulk of the story itself, I do think Neon White has interesting world-building and some cool ideas.

And hell, if you’re not a fan of the visual novel style, you can just skip the text. That’s easy enough. It’s still flow-breaking a little, but not nearly as much. I think the First Person Parkour of Neon White is good enough that it’s worth skipping half the game for — it really is that good.

But fair warning, if you do get it, or go back to it, you’re gonna struggle to beat my times. Not because they’re so good as to be untouchable, but because I don’t think you’re good enough. Consider the gauntlet thrown.